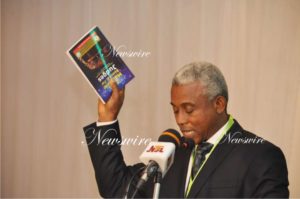

Book Review of the 14th Volume of the Maritime Seminar for Judges by Uwe Akan

The book is a compilation of the papers presented at the 14th Maritime Seminar for Judges held at this same venue from 31st May -1st June 2016. It is published by the Nigerian Shippers’ Council. I take this opportunity to appreciate the eminent jurists and legal luminaries who wrote and contributed to the important and topical issues considered in this 14th volume.

The book’s forward is written by Otunba Jimi Oduba SAN, a distinguished lawyer and a member of the Maritime Seminar for Judges Organising Committee. Included in this volume is the welcome address of the 14th Maritime Seminar for Judges, given by the immediate and past Chairman of the Maritime Seminar for Judges Organising Committee, Honourable Justice Ibrahim N. Auta, OFR.

Statistically, the Book is three hundred and thirty-six (336) pages long; it is divided into 21 parts with seven (7) chapters; it considers 6 (six) topics and has 5 (five) commentaries. The Communique of the 14th Maritime Seminar proceedings of 2016 is published in Chapter 7 of the book. It is the first time this is being done. I believe the purpose of its inclusion is to remind readers about the actions agreed upon at the last seminar, to enable them inquire or follow up on the recommended actions if necessary. The table of statutes, the index of cases and the word index of this 14th Volume, are more comprehensive I believe, than ever before. The book also includes International Commercial Terms (Incoterms), glossary of shipping terms, glossary of terms pertaining to multi-modal transport and port services terminologies among several other innovations.

The topic of the first chapter of the book is Introduction to Maritime Law and Admiralty Jurisdiction. The paper is written and presented by Hon. Justice Ibrahim Buba. The learned jurist and author previews the subject matter through an introduction which lays the foundation for the long discussion ahead. My understanding of the introduction is that the learned judge’s mind may be directed, perhaps, to State High Court judges appointed to higher office where they will come across maritime and admiralty issues or to those judges newly appointed into the Federal High Court who will inevitably preside over such matters.

Noting how uncommon this area of the law is, with its peculiar words, phrases and terminologies, the Honourable Justice sets out the meanings and circumstances of application of the various terms and illustrates with decided cases. As a consequence of the long history behind Admiralty Law and Jurisdiction, the learned author could not but step into the distant past to give additional insight and better understanding to the topic. In this regard he traces the Admiralty practice in Nigeria to its origins in English law and the adoption of the practice in Nigeria beginning with the Colonial Admiralty Act 1890 up to the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act 1962 which conferred jurisdiction on the High Courts. The distinguished judge also states that all matters pertaining to Admiralty law are being handed by the Federal High Court by virtue of Section 7 of the Federal High Court Act 1973 and section 251 of the Constitution of the FRN 1999 and that in matters of practice and procedure of the Courts, the Federal High Court of Nigeria, Admiralty Jurisdiction Rules 2011 applies.

The paper identifies and gives cogent explanation to some core terms, concepts and proceedings in admiralty Law with decided cases. It discusses proceedings such as action in Rem and in Personam, Arrest and Detention of Vessels, Caveat, Intervener actions, Limitation of Liability, Limitation of Actions, Maritime Lien, etc. He also explains the extent to which Maritime law and Admiralty Law are shaped by international conventions acceded to and/or domesticated by Nigeria.

The commentary on the topic is written by Mrs. Jean Chiazo Anishere. In her comments she draws attention to prevailing notions of interchangeability of the terms shipping law, maritime law and admiralty law and observes some subtle differences. She points out that there are areas of overlap noting that the terms are often given to oversimplification by categorisation. She highlights the aspect of Admiralty law dealing with marine cargo and prefers the extension of the Hamburg Rules, currently the prevailing law in Nigeria, to both inbound and out bound cargo. So far, it is applying only to out bound cargo. Another pertinent area of concern for her is the enforcement of cargo claims and the rules of the Federal High Court for enforcing such claims. She advocates the review of the M. V. Arabella case.

In Chapter 2 of the book Olumide O. Sofowora SAN, discussing the topic Electronic Evidence in Admiralty Practice, observes that electronic evidence has taken deep root in Admiralty matters even as far back as 2002 citing the case of P. A. Awolaja & Ors v. Seatrade Groningen B. V. (2002) 4 NWLR part 758. Drawing from Sec 84 of the Evidence Act 2011, which he sets out seriatim, he identifies the admissibility of electronic documents with or without oral evidence as the main issue involved in this section. The consensus of judges, he informs, is that oral evidence must be led in order to place such document properly before the court. He cites in support of this principle the case of Dr. Imoro Kubor & Another v. Honourable Seriake Dickson & Ors as per Onnoghen JSC (as he then was).

The distinguished Senior Advocate further raises the issue of what will be regarded as an original e-document tendered in evidence. He submits in his opinion that only the originator of the electronic document can tender it as original after complying with the provisions of sections 84(2) and 84(4) of the Evidence Act. He concludes that the effect of Section 84 is to make all the conditions stated therein to be proved before electronic documents can be admissible in evidence.

The learned Senior Advocate recommends in his closing remarks the adoption of some features of the Indian Information Technology Act 2000, such as defining key words pertaining to the computer lexicon which words are unknown to our Evidence Act 2011. This is because such words are necessary for a better understanding of computer generated documents. He suggests that Nigeria should enact a similar law in order to incorporate such terms into the Nigerian evidence law.

Chapter 3 of the book continues with Electronic Evidence but with special emphasis on the banking perspective. It is titled Electronic Evidence in Admiralty Practice- Banking Perspective, and is written by Barrister Patrick I. Oparah. Barrister Oparah expresses similar views on the Evidence Act as the Senior Advocate. With respect to banking in particular, he opines that Letters of Credit are equally electronic documents and should elicit the same standard of proof and evidence as provided in Section 84 of the Evidence Act. He raises concern generally on the issue of security of electronic systems and the absence of adequate laws to govern and regulate electronic communications and ponders the possibility of creating security interest in electronic documents.

In her comments on both papers on the Electronic Evidence, Mrs. Mfon Usoro reveals that as far back as 1976 the issue of electronic evidence was considered in the case of Yesufu v. African Continental Bank 1976 All NLR 264 at 273-274. She posits that the probative value accorded to electronic evidence in Admiralty Practice with reference to Section 34 of the Evidence Act, is the crux of admissibility of electronic evidence. She argues that as long as some weight can be attached to evidence in accordance with section 34 of the Evidence Act, there may be no outright inadmissible evidence of e-documents because oral evidence will be called to ascertain its probative value. On the issue of certificate, she counters any speculation that a certificate is tenderable orally. She maintains that it must be produced as a formal document first and foremost.

She also opines that any alteration of an e-document should cause it to be rejected in evidence as this will contravene section 16(1) of the Cybercrime Act.

In Chapter 4 of the book, the topic Addressing African Maritime Challenges is presented by Dr. Karem-Sumser-Lupson. The paper begins by noting the vast dependence on Information Communication Technology (ICT) worldwide and how this is affecting or changing the business of shipping in particular. These changes are so profound in terms of ship navigation, passenger and cargo tracking and discharge, port management infrastructure, etc.

The paper associates the innovation, technological and ICT transformation in the maritime industry to the work of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), which through its Committee, prepares the International Conventions adopted and implemented by the maritime member states. The implementation of the IMO Conventions in this regard, is making great improvements possible in the maritime industry in terms of efficiency of navigation, shipping business, port management and security. However, it is also being bringing increasing risk of information breach as information could be accessed, usurped or corrupted by cyber criminals. This often leads to disruptions in navigation, theft of funds or cargo. The presenter submits that the operations of cyber criminals are successful because of their infiltration of victim’s systems be it corporations, shipping lines or the management systems of ports.

The paper proposes that African maritime nations and stakeholders should work closely with the IMO to update their cyber security in the areas of access control, network design, intrusion detection, communication security and governance. African governments should also consider aligning and harmonising policies and be able:-

1. to carry out awareness campaigns

2. evolve common strategies and technologies for implementation

3. renew existing adequacies of cyber security

4. coordinate and cooperate; and

5. create information exchange platforms

In the comments on the lead paper, Chinwe Ndubueze confirms the reality of cyber threats but finds that according to a survey by International Business Machines (IBM) in 2008, they affect finance, insurance, manufacturing and ICT corporations more than the shipping or logistics sector. Notwithstanding this, there are instances of cyber attacks on ports, for example, the port of Antwerp in 2011.

The paper identifies security gaps in the ICT systems in use as the fault line which enables hackers and cyber criminals to have access to their victim’s systems. Another challenge preventing the fight against cyber threats is the reluctance of most victims to report successful attacks for business reasons. Furthermore, the paper notes that hackers are also getting more sophisticated in their exploitation of ICT knowledge and skills.

Chapter 5 focuses on The Role of the Nigerian Shippers’ Council in the Maritime and Transport Sector. The presenter Barrister Chibuzo Ekwekwuo, reviews in detail the background for the establishment of the Nigerian Shippers’ Council by Decree No. 13 of 1978 now Cap 133 LFN 2004. He restates the circumstances of international trade after colonial rule, which then adversely affected shippers in the newly independent countries of Africa and Asia, thus prompting the intervention on behalf of the shippers, of the United Nations Commission on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). By recommending the establishment of government backed Shippers’ Councils to act as a buffer between the shippers and the powerful shipping cartels, the writer maintains that UNCTAD successfully paved the way for the protection of the shippers in these countries.

The barrister also sets out and discusses the initial objectives of the Nigerian Shippers Council and its statutory functions under section 3 of its enabling Act. He highlights all the additional Regulations made pursuant to the Act over the years culminating in the regulation of the ports in 2015.

As a result of the expanded roles of the Council, it now performs various services including:-

1. stake holders/ industry support services

2. stakeholders representative services

3. information services

4. advocacy services

5. research/education/enlightenment services

6. complaint handling services

In his conclusion the writer believes that the services essentially fits those performed by a regulator. Accordingly, it is appropriate for the Nigerian Shippers’ Council to carry out the functions of an economic regulator in the maritime and transport sector.

The Executive Secretary of the Nigerian Shippers’ Council in his commentary validates the lead presenter’s viewpoints and adds further information and insight. On the role of the Council as a port economic regulator in 2015, he informs that at the time in issue, service providers in the maritime industry were charging excessive and arbitrary tariffs while not offering commensurate services. This was the basis for the Presidential directive to the Council to perform interim regulatory role at the ports with the backing of the Federal Ministry of Transport. The directive was confirmed by a Presidential Order published in the Federal gazette.

In my humble view, attention should also be drawn to the alarming failure of our legislative system to update Federal laws. Since 1978 the enabling Act of the Council has neither been amended nor repealed, even thirty years after. There is some resultant constraint, or even paralysis of the supervising institutions when the dynamism of their environment, in this case, the maritime sector, outgrows the legal parameters of the institutions to adequately manage it. That is why the Executive Secretary and those in office before him, should be appreciated for being able through proactive policy, direction and innovation, to lift the Council above the constraints and limitations of its stale enabling Act. Though its laws were and are still virtually obsolete to date, it is undeniable that the Council continually provides unbiased and unambiguously excellent services in virtually every area of its activities. Many may not know about the interventions of the Council which brought commendation to the Federal Government by a foreign nation. Nor will they have heard how through the intervention of the Council a foreign fraudster was arrested in Cotonou, Benin Republic and brought into Nigeria for questioning and prosecution over the issue of scammed and defrauded stock fish traders.

The National Assembly has recently passed a bill for the establishment of the Nigerian Transport Commission. The industry and stakeholders are all awaiting the signature of the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria to make it the law of the land. There is hope that the Council may transform, perhaps, into the Commission. Should this happen, it will be a fulfilment of a vision not only for the industry, but especially for the staff and officers of the Council, past and present, whose sacrifices would finally not be in vain.

The last but not least of the papers presented at the 14th Maritime Seminar for Judges is titled Legal Responsibilities of Operators in the Nigerian Ports (Nigerian Ports Authority, Terminal Operators, Shipping Agencies and Freight Forwarders). It is in Chapter 6 of the book and the presenter is Chief O. E. Nwagbara, a legal consultant. He cursorily looks at the history of the Nigerian Ports Authority pursuant to its establishment by the Act of 1956.

The author discusses the legal responsibilities of NPA under section 7 and the powers of the Authority as provided in section 8 of NPA Act. He also covers the responsibilities of shipping agents, freight forwarders and customs agents and justifies what they do and why they do so in accordance with their respective enabling laws.

As observed by the presenter, sometime ago, the issue of responsibility for wreck removal threw up controversy between some parastatals of the FMOT. What may not be known is the extent the Ministry went to resolve the matter including setting up of inter- ministerial committees for that purpose. Suffice it to say that even before the advent of the 2015 Nairobi International Convention on Removal of Wrecks referred to by the lead presenter, the recommendation to that effect had already been made.

Besides, it is important to appreciate that section 362 of the Merchant Shipping Act (MSA) 2007 provides for a Receiver of Wreck and as many assistant receivers as may be necessary. Since the MSA is administered by NIMASA, it is only obvious and fair that assistant receivers of wrecks in their respective areas of jurisdiction should coordinate with the Receiver of wrecks at NIMASA.

Chief Nwagbara also discusses the responsibilities of terminal operators in the temporary ownership and management of the ports particularly within the purview of the agreement between the terminal operators and NPA.

With respect to the responsibility of terminal operators at the ports, I observe, as has been observed and agreed at this forum, that the concession was hastily carried out without a legal framework and a regulator being put in place. However, with the recent review of the initial concession agreements, there is hope that the parties will be more able to achieve for themselves and the nation the original goals of the concession.

It may equally be important in this regard, to be mindful, in view of the enormous implications, of extending to foreign operators’ legal responsibilities in other aspects of the transport infrastructure such as Truck Transit Parks (TTPs) and Inland Container Depots (ICDs) and Container Freight Stations (CFS), which are being developed.

The commentary on Chief Nwagbara’s paper is presented by Barrister Emmanuel Achukwu. Mr. Achukwu’s comments from the outset, is wholly a critique of the lead paper.

He raises the question whether NPA can contract its legal responsibilities and cites M. V. Nordica & Ors v. Nigerian Ports Authority & Another which I think failed to answer the question in any meaningful way. In any case, Sec 8 of the NPA Act simply states so, that is, that NPA can enter into agreement to contract its responsibilities. In his discussion of the legal responsibilities of shipping agents the impression is that legal responsibilities can only be statutory. But this need not be statutory only; it can also be contractual. (see definition in Black’s Law Dictionary 6th Edition). Finally, the argument that the lead not presenter exceeded the topic by including customs brokers or clearing agents (which are specifically mentioned in the topic) may not be fair as the lead presenter is still within the ambit of the topic to do so.

CONCLUSION

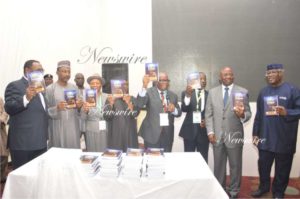

The above review of the 14th book of the Maritime Seminar for Judges clearly suggests that topics and titles of interests are covered in this volume. I must say that they are written and commented upon by the elite cream of the judiciary, practicing lawyers and maritime experts. The 14th book of the Maritime Seminar for Judges is available both in print and CD ROM.

As a record of the main event of the seminar, the book is unassailable in quality and content and will be useful for research to all practitioners, judges, operators in the maritime industry, law teachers and students. It should be a staple in the legislative libraries of the States and the National Assembly.

Your Excellency, My Lords, and Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, it is with all pleasure that I recommend to you this 14th Book of the Maritime Seminar for Judges.

Uwe Akan

B. A. LL.B. LL.M. BL

Also Read: Afba Reveals Hotel Partners / Provisional Program Schedule 2018 Conference Sessions

Also Read: Commencement of Registration Nigerian Bar Association 2018 Annual General Conference/

Subscribe for your copy/copies now

Do you need to be heard? Or your articles published? Send your views, messages, articles or press release to: newswiremagazine@yahoo.co.uk >>> We can cover your (LAW) events at the first Call: 08039218044, 08024004726

-Advertisement-

Grab our latest Magazine, "Chief Wole Olanipekun, CFR, SAN, A man of wide horizons and deep intentions". Get your order fast and stress free.

For more details about Newswire Law&Events Magazine, kindly reach out to us on 08039218044, 09070309355. Email: newswiremagazine@yahoo.co.uk. You will be glad you did